- By Ana

- May 20, 2020

- 7:57 am

Interview With Author Thomas J. Rice

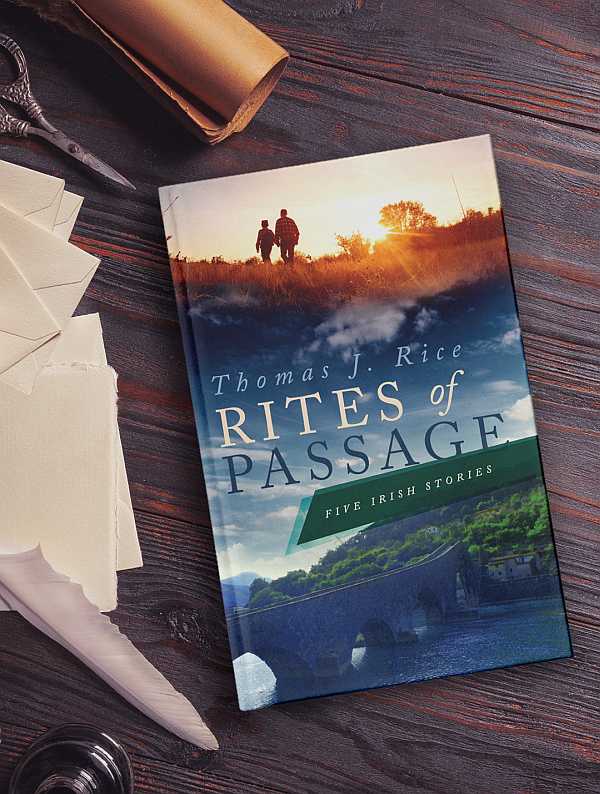

When I first met Thomas J. Rice, back in 2016, he had already finished writing his novel “Rites of Passage: Five Irish Stories” and was looking forward to offering it a representative, striking cover art. I was fortunate enough to inspire Thomas with my portfolio and so the seed of our collaboration took root.

An Irish-born writer with an incredible talent for expressive storytelling that abounds with elaborate characters, Thomas J. Rice’s novels will keep you on the edge of your seat.

Hi, I’m Ana Grigoriu-Voicu, book cover designer to independent and best selling authors all around the world. My focus lies on creating powerful visual stories for your published masterpieces. Via my blog I’m aiming towards providing you with the unique artistic perspective of someone who wants to turn each project into a best-seller. If you want to find out more about my work or you’d like to stay in contact, feel free to connect with me over Facebook, Instagram or e-mail.

You’ve published three books so far, with one more currently in the pre-publishing phase. What is your main source of inspiration?

The wellspring of inspiration for me is my Irish upbringing. I grew up in a storytelling household where the oral tradition—one that goes back centuries—was on nightly display.

My mother married into what was known as a “rambling house,” which meant that every night our neighbors would “ramble” over to our kitchen where storytelling, poetry, music, step-dancing, and card playing would be all part of the mix. We had some wonderful native talent, always with a flair for the dramatic, who could not wait for their turn to perform.

Besides that magical childhood (till I was 16), I find my inspiration in Irish writers and really all great storytellers from around the globe. I’m partial to the Irish idiom, of course, since I find them unique in the world of literature. Some classic examples: James Joyce(Dubliners; Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man; Finnegans Wake);Sean O’Casey’s Plays( Juno and the Paycock, etc.); William Butler Yeats’s poetry( The Song of Wandering Aengus; Lake Isle of Innisfree); Patrick Kavanagh’s memoir, The Green Fool, and his evocative poem/song, Raglan Road; Kevin Barry’s, There Are Little Kingdoms.

How did you begin writing? What sparked your interest in becoming a writer?

I’m a sociologist by training, a profession not known for its page-turning prose or evocative scenes. As a student I found it a distinct advantage to be able to write well—in any discipline—with an audience in mind, in contrast to the “dry toast” that social science favors. Over the years I found my writing increasingly hamstrung by the conventions of the discipline, like a bird with a broken wing. I began writing short stories(fiction) as a form of relaxation and entertainment. And I was delighted to find that people enjoyed my writing. So, I made the break around 2007-08 with a memoir about growing up in rural Ireland.

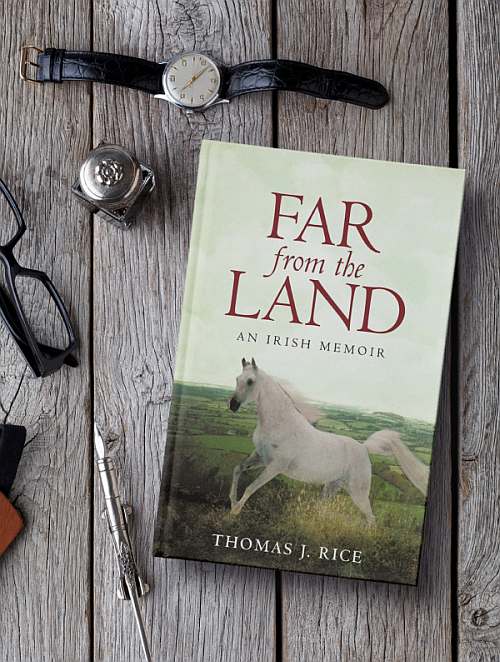

“Far from the Land”, your memoir set in rural Ireland in the mid 20th century reminds the reader of a way of life that seems so far removed from our current reality. How did you feel writing about and revisiting that period in your childhood?

I started writing it late one night after I’d read a heart-rending newspaper account of a farm family eviction in Minnesota. It reminded me of our own auction, when we decided to leave Ireland. I was surprised by the clarity of memories it stirred, and from there the memoir practically wrote itself (That first chapter was published as a short story. It’s called, “The Last Laugh,” published in Green Hills Literary Lantern, 2019). The rest just flowed like a river, gathering force and shaping its own narrative as it went along. It felt exhilarating and very satisfying, a chance to honor the people and the country that shaped so much of my life. Also, I wanted to educate my readers about a culture that is now almost extinct. I say almost because there are still remnants of that post WWII Irish culture to be found in contemporary Ireland—most notably in the western province, Connaught.

“Far from the Land” is available at Amazon as e-book, paperback and hardcover.

Thomas Rice takes us back with him to his ancestral home — and to the excitements, dreads and legends of childhood in a rural village. At the end of each story, after I settled down from the chills and tears, the author bid me good night with a wink and a nod.

— Barry R., Rites of Passage: Five Irish Stories

“Rites of Passage”, your collection of two novellas and three short stories centers around the themes of corruption, terror, hope, and redemption. The second novella in the book, “Hard Truths,” was featured in The Best American Mystery Stories of 2012. How do you approach character building? Do you outline the characters’ traits before starting to write a story or do you let them develop on their own as the story progresses?

As a general rule, I follow the approach recommended by Lajos Egri in his seminal book, “The Art of Dramatic Writing.” He urges writers to construct detailed character profiles focused on three main areas:

-Physical (appearance, sex, race, age, health).

-Psychological (love, hate, fear, pride, shame, guilt, success, failure).

-Sociological (social class, education, occupation, family, friends, religion, politics).

However, I don’t begin with a list of facts about my character such as eye color, height, marital status, attractiveness, etc. Rather, I follow the approach of David Corbett (“The Art of Character”)where he suggests that it’s best for the writer to envision these attributes in a dramatic scene, focusing on the question: “How does my character’s physical, psychological and sociological makeup affect her interactions with others.” For example, in “Rites of Passage,” we first get to know my protagonist, Billy Donovan, by his own memory of being abused as an altar boy in a rural community.

The reader learns the relevant information about Billy through his own recollection of the actions he took as a boy, and the action he takes in confronting his abuser 25 years later, now as a successful professional. So for me, the key to character development is in the action; reflections and introspection are important, but they only go so far. It’s in the action—what they do and say—that a character reveals the true self, rather than in what he thinks and feels. That’s because thoughts and feelings are ephemeral. They can be superseded, cancelled, or countered in an instant. Not so with words and deeds. They call for commitment. They have consequences. They define character.

Ultimately, character development comes down to a cardinal rule of writing: Show, don’t tell. Granted, telling the reader what a character is thinking and feeling is important. But it’s far less effective than showing how it influenced his behavior, or showing him grappling with those ideas and emotions in such a way that it leads to meaningful, consequential action. Consider this: Would Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov (“Crime and Punishment”) have been such an unforgettable character if all he ever did was think about murdering the old pawnbroker, Ivanovna? Would Nabokov’s Lolita have been such an enduring sensation had Humbert, the narrator, never acted on his obsession?

Purchase Rites of Passage at Amazon as e-book and paperback.

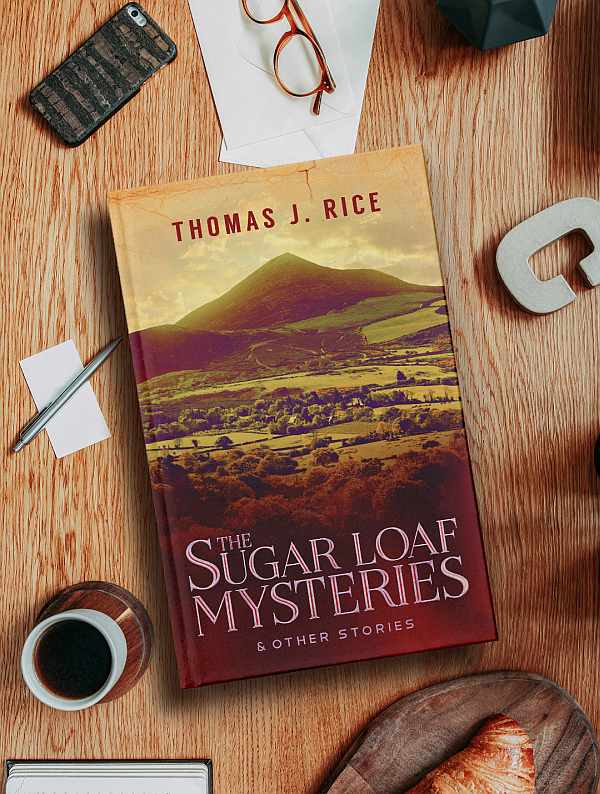

Your latest title “The Sugar Loaf Mysteries & Other Stories” is considered a sequel to “Rites of Passage”, how did you approach the narrative of these six mystery novellas this time around?

To be clear, this latest collection has two novellas—book ends to the seven stories— and four stories about life in rural Ireland during the 1950s. A seventh story —it’s called “Dancing with the Devil”— is the first story I’ve written that does not have an Irish setting or Irish characters. It’s about a hard-charging, principled young journalist who suspects foul play when an oil rig explosion claims the life of 11 workers in the Canadian Northwest. It was inspired by my work as a sociologist doing research during the ‘70s. As with all my stories, I particularly enjoyed the plot twists and surprise ending of this one. I hope the reader finds all seven stories entertaining and well worth the time.

What part of a story do you usually find the hardest to write?

The opening pages. That’s the place where any number of ideas and questions are competing for space in my brain. Do I start with an expository backstory, or with a bold action? Do I start with dialogue that engages the reader, or with a vivid overview of character in setting? Do I reveal or foreshadow the plot and if so, to what extent? How much specific, intimate detail to include? Whose point of view (POV) is going to narrate the story? How many plot strands am I going to launch? How will I plan on landing them? When do I reveal the core desire of my protagonist? Her secret vulnerability or character flaw? What obstacles will I introduce to stoke the “rising action”—suspense toward an eventual climax? How subtle (or blatant) will my “inciting incident” be to frame the emerging plot?

The decisions I make—the architecture of the story—become the cornerstones that I set forth in that opening section. Like the blueprint for a building, if that first pilon is off, I’ll soon run into a cul-de-sac and waste a lot of time and energy. It’s why I don’t start writing until a story is really “cooked” in my ruminations—sometimes decades worth—and the urge to write becomes almost an ache. I also think it’s an effective antidote to writer’s block.

The Sugar Loaf Mysteries is available at Amazon as e-book and paperback.

What do you think about the concept of writer’s block?

It’s a complex topic, given the mix of scientific and nonscientific opinions about its origins, consequences and treatments. I’ve never experienced writer’s block, but I have great empathy for those who have, and I see it as an insidious (crippling, invisible) affliction. From what I’ve observed and read about it, two things stand out: one, it is thoroughly debilitating to untold numbers of highly gifted people, and there is no doubt that it should be seen as a serious issue for many writers that has not been given enough attention. Two, a major obstacle to progress is a strong prejudice (at least in American culture) that writer’s block is “all in your head” and that the real problem is a lack of motivation. Rather than wasting time convincing the skeptics, my approach would be to support the work of neurologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and other scientists who show promise of bringing compassion, insight, and relief to the victims of this malady. After all, it’s not just the victims who lose out. All of society is denied access to the gems and masterpieces such artistic geniuses are blocked from producing. Think of Maya Angelou, John Steinbeck, Leonardo DaVinci, Joyce Carol Oates, and Pierce Colbert as examples of what we’d never have read, seen, or heard had they been so afflicted.

“Perseverance is essential to success. Keep writing and trust that good things will happen.”

— Thomas J. Rice

What is your writing setup and do you have any kind of “writing ritual?”

I have a writing desk in a secluded part of our house and a regular routine. I go the gym first thing after breakfast, six days a week. I come home, have lunch, do whatever routine tasks (email, phone calls, etc.) get to my writing desk by 1p.m. No phone, no emails, no distractions, until 4p.m. I have a very talented editor, my wife, who keeps me from major embarrassment as my trusted first reader. I also have a professional editor, a faculty member I met at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop in the summer of 2010. He’s been my inspiration and mentor ever since.

Before I start a major writing project, I have an agreement with him for the following: I will produce a set number (15-20) of “clean pages” every week and get the first draft to him by, say Friday. He will have read it and made detailed comments by the following Tuesday, in time for our phone conference in the afternoon. We go line-by-line over the draft (pros and cons) and I come away with a commitment to have two products by that Friday: the second draft (complete with upgrades), and another 15-20 pages of first draft material. We proceed until the project is complete, which is when he says it’s ready for publication.

In parallel with my writing, I read other authors I admire and whose work inspires me. For example, if I’m working on a piece about social justice and the underdog, I might reread John Steinbeck, Upton Sinclair and Charles Dickens. Similarly, if I’m working on an Irish short story, I’ll may reread John McGahern, William Trevor, Colm Toibin, etc.. The point is to let the style and genre sink into your limbic system, so it permeates your whole being. Also, it sets a standard: you don’t want the gap to be too wide between some of your best work and theirs. If it is, you must keep rewriting until you arrived at the desired threshold.

What is the best piece of writing advice you’d give some that has just started writing?

I don’t know if I have a “best piece of advice.” I’ll leave that to the oracles and mystics. But here are some things that worked for me in learning the craft of writing:

Read everything you can lay your hands on, especially by authors you admire and find inspirational. There are no great writers who are not also great readers.

Invest in “How To” reference books about the craft: Here are a few of the best I found:

- Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

- Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

- Natalie Goldberg, Wild Mind: Living The Writer’s Life

- William Zinsser, On Writing Well

- Lajos Egri, The Art of Dramatic Writing

- David Corbett, The Art of Character

- John Gardner, The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers

Commit to a discipline of writing every day, same time, same place, for a least an hour. It doesn’t matter what the quality level is at first. Just sit and write, write, write. Silence your inner critic. Get the pages cranked out. Quality will come.

Go to writing workshops (at least one a year) that are run by established writing teachers.

Find a trusted reader whom you like and respect, someone you can count on to give you constructive feedback. It’s the fastest way to develop your skill.

Take courses on-line using the Coursera website. This is a free learning resource that is invaluable, especially for aspiring writers new to the craft. For example, Wesleyan University offers an outstanding series on Creative Writing featuring such celebrated authors and teachers as Brando Skyhorse, Amy Bloom, and Salvatore Scibona.

Be prepared to pay your dues—10,00 hours, according to Malcolm Gladwell—before you can call yourself a writer. This is not a craft for the dabbler or faint of heart. It’s all about sweat equity.

Perseverance is essential to success. Keep writing and trust that good things will happen.

What book is currently on your nightstand?

Actually, there’s a stack of about 25. But on top of the pile is Bruce Springsteen’s memoir, Born to Run and Colm Toibin’s , Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know: The Fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce.

Where can we follow your work on social media?

My website is, barrowriverpress.org.It lists all my books and a monthly blog post that my readers find interesting. Also, I use Facebook to announce new publications and the usual give and take.

Share this article: